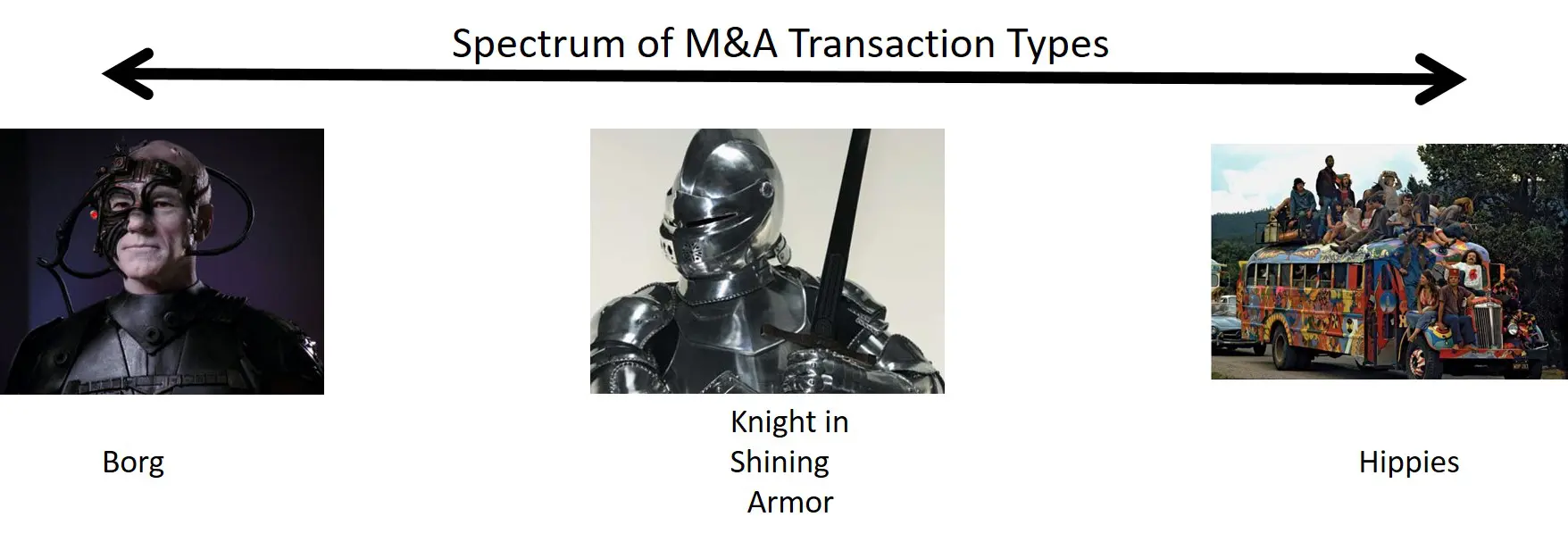

Tech M&A is on the rise. In the first quarter of 2021 there were 724 software M&A transactions. 354 of these deals involved SaaS companies SaaS. Valuations are at an all-time high. The median Q1 2021 Enterprise Value/Revenue (ttm) multiple was 14.2x. Deals in the Dev Ops and I.T. Management segment had a median EV/Revenue (ttm) of 31.5x. Product managers should be prepared. There are many approaches acquirers use to M&A. Computer Associates had one approach that many considered to be harsh. Others had a friendlier, kinder approach like the style employed by Google and Apple. Still others like Vista Equity Partners had a third approach – growth equity. For product managers having their company being acquired is potentially one of the most challenging events they will face in their career. It is important for product managers to understand the M&A style and approach a potential acquirer may employ. In this post we will look at the spectrum of M&A approaches and dive into the three cases– what I call the Borg, Knight in Shining Armor and the Hippie approach. In the spirit of full disclosure, I was a M&A exec for three enterprise software firms. I led three Borg-like acquisitions, one Hippie acquisition, and 11 Borg like divestitures.

•

The Spectrum of Tech M&A Styles

There is no single approach to M&A. Each acquirer has their own motivations and style. One can think of a spectrum, with extremes at either end and some type of middle way. Product managers should learn about these different approaches and how they could impact them. For a basic primer on Tech M&A check out Product Managers: How to Survive an Acquisition and M&A Integration War Story.

The Borg

The Borg approach was pioneered in the late 80’s and 90’s. Example acquirers included Computer Associates, Platinum Technologies, and Sterling Software. This approach was characterized by:

- Complete takeover of a company’s operations.

- Significant headcount reductions and office closures

- Significant reduction in new product development and often customer service

- Financial engineering (junk bond style debt to finance acquisition)

- Annihilation of acquired company’s brand an identity

- Replacement of acquired company’s management with exes and managers from acquirer

- Primary focus was on increasing profitability, EPS, and Enterprise Value.

In the 1980s and 1990s these firms sought out what they considered to be undervalued companies and acquired and subsequently restructured them. Often these firms had struggling stock prices, poor financial performance, and potentially liquidity problems. They could be acquired at a discount to their intrinsic value and restructured into profitable enterprises. Their approach was a precursor of the infamous Chainsaw Al Dunlap. Many of the companies acquired in this period had been successful at one time, but had fallen on hard times due to changing market conditions (client/server and Internet revolutions), investments in new products that ultimately failed, or botched acquisitions.

The primary driver of these acquisitions was the growth of shareholder value. Most of the senior executives of firms like CA, Platinum, & Sterling had a significant portion of their personal wealth tied up in company stock and stock options. Their business model succeeded as long as they could find undervalued companies that they could restructure to profitability they could drive up the value of their stock and personal fortunes. The Dotcom bubble ended their business model with the stratospheric valuations of the late 1990s and the year 2000.

From a product management perspective, Borg-like acquisitions are the riskiest. Product managers are faced the chance that their product could be eliminated or have its funding significantly reduced. Often senior product leadership is replaced by managers and execs from the acquirer.

The Hippies

At the other end of the spectrum are the Hippie acquisitions. These deals, often done by West Coast software firms, were focused primarily on the products and not profits. Hippie deals were characterized by very high valuations and focused on products, not the financial characteristics of the business. Typical acquirers were the FAANG companies –Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google. A quintessential example is Google’s 2006 $1.65 billion acquisition of YouTube. YouTube had been founded a year and a half before and had raised $85 million in venture capital. They had 65 employees, but controlled 46% of the video streaming market. Google had been struggling in that market with Google Video. The YouTube acquisition was a huge bet, but it enabled Google to dominate the video streaming market. In 2019 YouTube had grown into a $15 billion business.

The Hippie approach is characterized by:

- Extremely high valuations, often paid for with stock (versus cash/debt for Borg acquisitions)

- Primarily focused on products versus revenues/profits

- Acquired companies left intact, often as a strategic business unit of acquirer

- Little to no headcount reductions

- Focus on integrating/leveraging technology and human capital

- Significant resources invested to accelerate growth

- Significant growth opportunities for employees of acquired companies to move into new positions in the acquirer’s company

The following is an email exchange between Mark Zuckerberg and David Ebersman Facebook’s CFO around the time of the Instagram acquisition. It is a classic example of how Hippie-style acquirers think and what they value the most:

Product managers can face a few challenges in Hippie acquisitions. While their product management organization may be left intact, they may have to adapt to the acquirer’s product management approach. Product management styles can vary significantly between enterprises – from Lean Startup to Pragmatic Marketing to the Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe). A product management team may have to learn a new approach to fit into their new organization. A second challenge is the ‘Big Fish, Little Pond’ scenario. Prior to the acquisition, product managers are often the big fish in their company’s pond. They have significant influence, are respected, and have a direct impact on the company’s total success. Post-acquisition they may be just one of hundreds, if not thousands of product managers in the new organization. Some product managers have a hard time accepting being a ‘little fish’ in a huge ocean. These individuals tend to leave and join smaller enterprises where they feel more comfortable.

Knights in Shining Armor

The Knights in Shining Armor approach is a hybrid of the Borg and Hippie approaches to Tech M&A. It is often associated with Growth Equity. Growth equity investors (private equity firms) focus on creating value through profitable revenue growth within their portfolio companies. Vista Equity Partners’ acquisition and subsequent sale of Marketo is often cited as a prime example of this strategy. The following table illustrates the differences between Venture Capital, Growth Equity, and LBOs:

The Knight in Shining Armor approach is characterized by:

- Established companies that have fallen on hard times, often public companies that have taken a stumble

- Premiums above current market valuation often paid

- Deals most often involve equity and little debt

- Restructuring to achieve profitability

- Replacement of senior executives and key managers is common

- Introduction of best practices from investors other portfolio companies

- Primary focus is on changing strategies and execution to focus on sustainable revenue growth

- Goal is to significantly grow enterprise value

- Exit in 3 to 5 years, often to strategic acquirer

Vista Equity’s acquisition of Market for $1.8 billion and its subsequent sale to Adobe three years later for $4.75 billion is often cited as a classic example of successful growth equity investing.

Marketo was a provider of marketing automation solutions. It targeted the entire spectrum of enterprises – SMB’s, mid-market companies, and large scale enterprises. Marketo went public in 2013 and by early 2016 their revenue growth had slowed considerably and their stock price had significantly declined. Marketo was trying to fight a battle on too many fronts – from SMBs to large scale enterprises. Their competitors, like Hubspot (SMBs) and Salesforce (enterprises). They were consistently unprofitable. In the Spring of 2016 management and the board began a process to sell the company to a strategic acquirer. Vista offered a 67% premium to the then current stock price and beat out six other bidders.

Vista implemented a number of Borg-like actions to reduce Marketo’s expense base and return the company to profitability. They deployed an updated version Vista playbook which focuses on leveraging best practices of their portfolio companies. On the growth side of the equation, Vista replaced the founding CEO of Marketo, Phil Fernandez, who had been running the company for a decade. His replacement, SAP executive Steve Lucas, had more experience with reinvigorating the growth of a software business. The company revamped its product development and decided to go after large deals in the enterprise space, where retention rates are higher and upselling is easier. In 2017, Marketo’s revenue grew to about $321 million from $209 million in 2015 and by the start of 2018 the company was generating positive EBITDA; it was posting -$50 million of EBITDA in the 12 months before the Vista acquisition. In August 2018 Vista announced the sale of the revamped Marketo to Adobe for $4.75 billion. They netted almost $3 billion in a little over two years.

Product manages face a combination of challenges in Knights of Shining Armor acquisitions. It is a combination of the challenges they face in Borg acquisitions (product elimination, headcount reduction, investment reduction) and the challenges of Hippie acquisitions (new product management approaches, big fish – little pond). Generally, the worst aspects of Borg-like acquisitions (reduced customer service, reduced R&D investment, etc.) are avoided.

Summary

Mergers and acquisitions are perilous times for product managers. Decisions made by others, with little or no input by product management, will determine the fate of your products, your pocketbook, and even your job. While there is a chance that your product will be negatively impacted, there is an equal chance that a merger or acquisition will create new, positive opportunities for you.

Product managers need to prepare themselves for the possibility that their company could become involved in an acquisition. Check out M&A Basics for Product Managers, Product Managers: How to Survive an Acquisition and M&A Integration War Story.

Also published on Medium.